The Mathematics of the Guidelines

The following are excerpts from the Report on the mathematics of the Guidelines. The Formula may seem intimidating at first reading, but it is only junior high math and reads much more simply once you are very conversant with terms used.

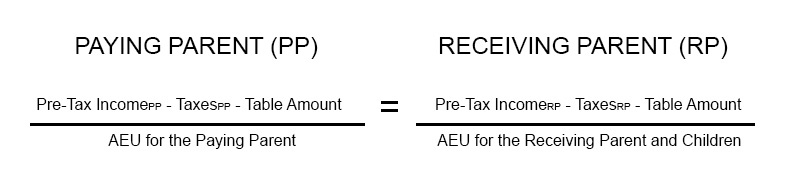

The DOJ claims that the Formula used to determine the child support awards is intended to equalize the “living standards” of the two households following a marital split if the income of the paying, NCP is equal to the income of the receiving, CP.

In the Formula, AEU stands for adult equivalent unit. An AEU is simply a number which reflects the “equivalency” for different sized families consistent with the equivalence scale one is using. In this case, the Formula uses a 40/30 equivalency scale, where 1.0 is the AEU for one person living alone, 1.4 is the AEU for a single parent and one child; 1.7 is the AEU for a single parent and two children, and each additional child adds .3 to the costs. The “living standard” of a household, according to this Formula, is its after-tax income (plus or minus child support payments, as the case may be) divided by the AEU value. This equivalence scale also tells us that all the available funds in a household are spent and that a specified percentage is spent on the children (.4/1.4 or 28.6% in the case of a single parent family with one child, .7/1.7 or 41.2% in the case of a single parent family with two children, etc.).

The Formula is solved by assuming that both parents have exactly the same pre-tax income (at every level of income). However, it is solely the income of the NCP that is used to set this assumed equal amount of income. The CP’s actual income is completely ignored (i.e., it is always assumed that the CP’s income is the same as the NCP’s income).

This assumption of equal incomes may initially seem to work against the CP, but that is incorrect for two reasons. Firstly, the formula cannot be solved unless an assumption is made with respect to the relative standards of living after the child support payments. This would be arbitrary and contentious if the initial incomes were not equal, but it is not contentious that the standards should be equal after child support if both parents earn the same amount. This actually just creates a fixed percentage which is then used at all levels of NCP income, regardless of the CP’s actual income.

The second reason the equal income assumption is not prejudicial to the CP is that it is only one of a number of assumptions, such as ignoring most government benefits for children, all of which are received by the CP. Any costs of the children borne by the NCP are also ignored. The impact of these other assumptions dwarfs the equal income assumption.

Except for the moderating effect at lower incomes due to the only government benefits that are factored into the Guidelines, the formula results in 16.7% of after-tax income of the NCP being payable for one child and 25.9% being payable for two.

Do The Numbers Add Up?

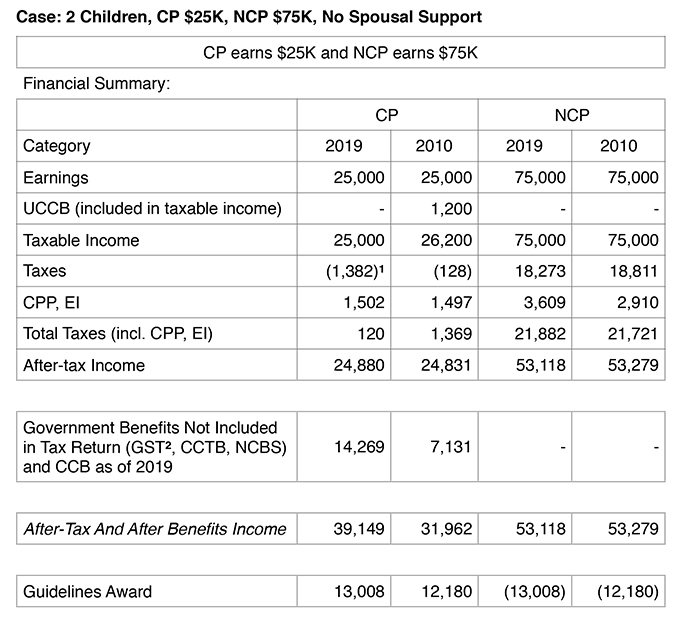

What follows is an analysis using:

- the 40/30 scale for the assumed costs of children;

- the comparison of the parents’ disposable income; and

- the breakdown of the relative shares of support for two children using the template (the “Newfoundland Illustration”) set out by the DOJ itself in 1996 (in earlier draft versions of the December 1997 Technical Report), but with a CP income of $25,000 and NCP income of $75,000.

In the Newfoundland Illustration, the DOJ is showing three things: (1) how the cost of the children is calculated at a given income level; (2) how the cost of the children is shared between the CP and the NCP, and; (3) which of the two (post-separation) households has the higher standard of living.

It is worth re-emphasizing that the Formula specifies the shares of after tax, after benefits and after child support income allocated to children (for example, 41.2% for the (2) children plus 58.8% for the single parent) sum to 100%.

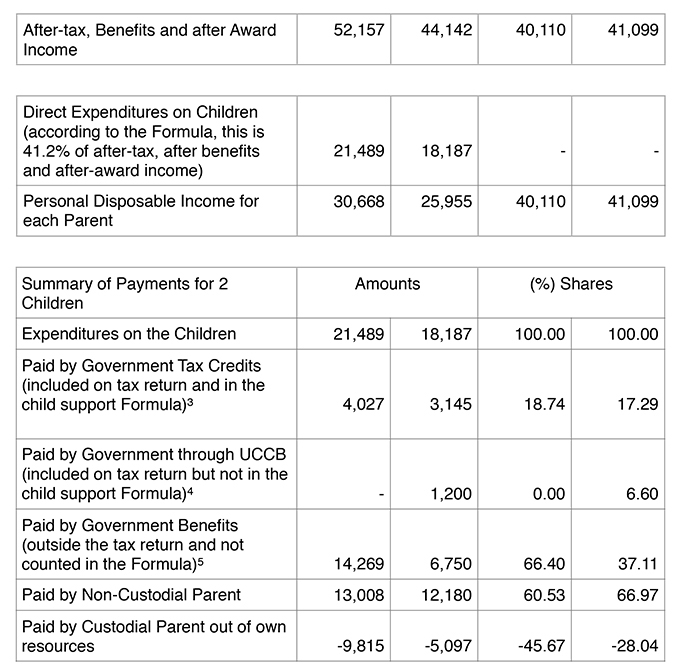

Exhibit 10 of the Report is reproduced below with figures from 2010 and updated figures from 2019.

Note 1: Taxes are zero and the amount represents the results after applying the Working Income Tax Benefit.

Note 2: GST rebates include the Newfoundland Low Income Supplement.

Note 3: “Paid by Government Tax Credits (included on tax return and in the child support Formula)” – represents the amount federal and provincial taxes are reduced by tax credits attributable to the children.

Note 4: “Paid by Government through UCCB (included on tax return but not in child support Formula)” – is the after tax impact of the receipt of the Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB).

Note 5: “Paid by Government Benefits (outside tax return and not counted in the Formula)” – represents the amount of the non-taxable government benefits (i.e. GST, Child Tax Credit Benefit (CTB), National Child Benefit Supplement (NCBS) received that relate solely to the children.

The example above shows the case of a NCP earning three times the pre-tax income (or 200% more) of the CP. For 2019, the NCP’s share of the total assumed spending on the children is now 60.53% and the CP’s share is actually negative (-45.67%). So, not only does the CP not have to contribute to the children’s costs but actually makes money on the child support.

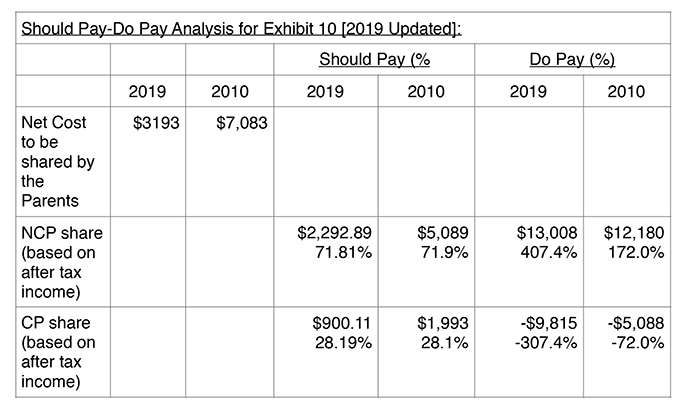

At this point, it would be useful to compare what share of net child costs is being paid by each parent as against what should be paid based on each parent’s “means” or relative ability to pay. For this purpose, the Report defines “net costs” precisely the same way as the DOJ, that is, as the amount deemed to be spent by the parents on the children after first counting the child related government contributions (tax credits and deductions, including provincial programs) as having been spent on the children. In determining the amount that “should” be paid by each parent, which requires a determination of their relative after tax means, the Report excludes from their means those government benefits that they may have received but which have already been accounted for as having been spent on the children. Described another way, the “should pay” amount is based on relative after-tax income after removing all government benefits/deductions related to the children. For the purpose of the Report, this is considered to be the parent’s relative abilities to contribute or simply their “means” for short.

Applying the “should pay-do pay” analysis to the example above, the results are summarized in the chart below:

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ON HOW THE GUIDELINES ARE ACTUALLY ADMINISTERED

The link below is a summary by a family law expert in Ontario with respect to certain aspects of family law that are applicable across Canada, except Quebec.

Reports

Coming soon.